If I invite you over for dinner with my family, be warned, it tends to go like this: we have wine, and then we start talking about the Holocaust.

Most of the time my family has a sarcastic allergy to the serious, so when I try to warn friends, they rarely believe me. It’s only when we’ve each sunk half a bottle that a morbid undercurrent starts pulling us inexorably into the past and towards Eastern Europe. Then my guests realise I wasn’t joking.

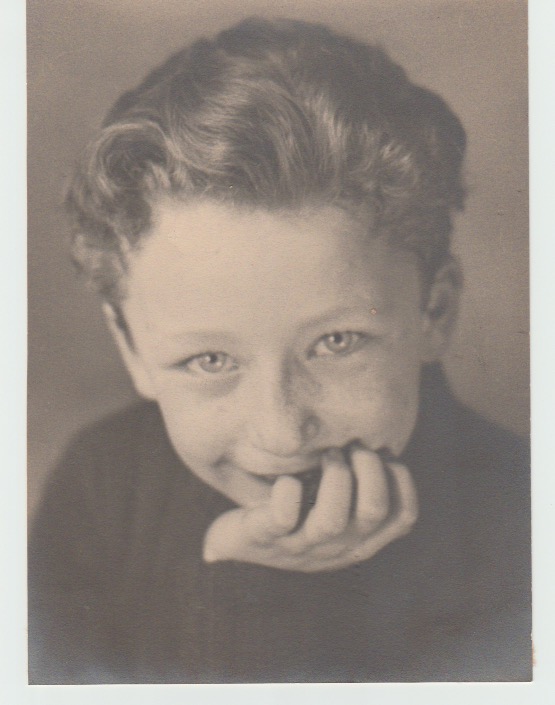

I grew up with only a vague sense that my paternal grandfather, who we all knew as George, was from some other place across Europe, somewhere cold and far away. Confused by our surname, when I was very young I would tell people he was German. My dad soon corrected me: George was Polish. I was a happily self-absorbed child and only half-listened to his stories, which would meander between a childhood in Krakow, the RAF in Egypt, moving to the UK. Sometimes he spoke of Karolina, his mother and a poet who, he told us, had let herself be blown up in Warsaw rather than let the Nazis take her.

George’s real name was Jerzy. He died in his nineties, but not before my parents, aware time was running out, sat with him over a week or two at his home in Sussex and recorded all of his stories. At some point the tapes were lost in a house move. I had never made time to listen to them.

In my early twenties, years after George’s death, I moved to Paris. My parents came to visit, and between eating patisserie and sweating up the endless flights of stairs to my apartment, we went to the Holocaust memorial. There’s a huge black marble wall with the names of the victims deported from Paris engraved in gold. There was our name: Wasserberg, Ignace. George’s father. My dad stroked the letters on the black marble and went uncharacteristically quiet.

Later, in a tiny bistro in Pigalle, we talked through the details, my Mum supplying things George had told her when they recorded the tapes. Ignace had been safe in Switzerland, but inexplicably travelled to France in 1942, into the mouth of the tiger. Perhaps to check on a property there, George had thought. He was arrested as a Jew, sent to Paris, then Drancy, and then on to Auschwitz. We sat together obsessing over the moment Ignace realised his catastrophic mistake. Was it as soon as he was asked for his papers? In the train to Paris? At Drancy? Or did he think, up until the last moment, that this was all some administrative error, that someone would be waiting for him in a car beyond the barbed wire? These questions joined fragments of other family stories as my novel The Light At The End Of The Day was taking shape.

The painting at the heart of the novel hangs in the Museum Narodowe in Kielce, Poland. The little girl stands in a scarlet dress with ballooning short sleeves, her hand resting on the back of a dining chair. A glossy cascade of blonde hair pours over her shoulder as she looks into your eyes with an expression that is hard to read. This is Josepha Oderfeldt: Ignace’s daughter, and the sister of my grandad’s mother, Karolina.

Josepha survived. On a trip to Krakow in 2016, I met Josepha’s grandson, and her great-granddaughters, my cousins. We ate bagels and made small talk in broken English and French, and looked at photographs and family trees with branches that broke off again and again in 1942. I felt we were scattered shrapnel from an explosion long ago. Back home in England, I hung a print of the painting, the red brightening my tiny kitchen, and began writing about Josepha. She became Alicia, and Ignace became Adam. Around them, around Karolina, and around the painting, I told a story.

From the seeds of George’s and Josepha’s truths I’ve sown a fiction that I wrote to try to somehow heal the hurt in my dad that keeps going back to that gold lettering on the black marble wall. Perhaps I’m also trying to make up for my adolescent half-listening to my grandad, whose stories persist only in family memory. I hope reading it is a little like having dinner with my family: enjoyable and rich like good food and wine, until you realise you’ve been pulled unexpectedly into a world that’s already gone, filled with orphaned voices and unquiet images that echo down the generations.

Get a copy of The Light at the End of the Day now.

Follow Eleanor on Twitter.