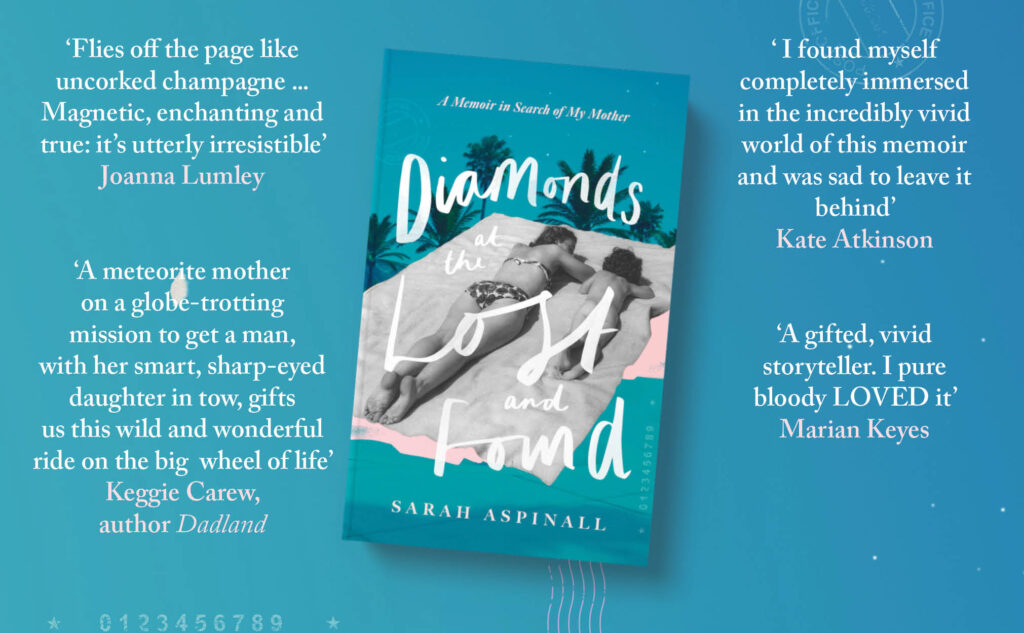

For readers of Hideous Kinky, Dadland and Bad Blood; the astonishing, beguiling story of Sarah Aspinall’s harum scarum childhood, and a love letter to a woman who defied convention to live a life less ordinary.

The stories my mother, Audrey, told about her own past, and later those I began to tell about my own unconventional life growing up with her, would always be greeted with peoples’ gasps of amusement, disbelief or even horror. Then the questions would begin – ‘so where was she getting all the money from? ‘How did she get to meet Frank Sinatra?’ Or ‘Why were you living in that weird motel in the Killdevil Hills, North Carolina?’ ‘That’s a fantastic story!’ they would say, and when I saw them again, ‘I really want to read that book!’

For years I didn’t believe I could do it, and anyway I was too busy juggling my job making documentaries with bringing up our children, so it was only when they finally flew the nest that I decided to take the plunge.

I’d just spent a few weeks with Booker prize winner, DBC Pierre, filming our road trip through the US and Mexico, and on the way I entertained him with this same childhood story. He not only said ‘you have to write that’ but also, incredibly, ‘I’ll help you’ and over the next year or two he was as good as his word, becoming an amazing mentor and friend.

He encouraged me to search out the truth and be ruthlessly honest, but also to make up dialogue and create scenes in a novelistic way. He pointed out that of course I can’t remember what was said in the bar of a Hong Kong hotel when I was eight years old, but it was the emotional truth of that moment that I needed to recreate.

After decades of making real life films I soon realised that there was an exhilarating freedom in being able to shape the material in this way. I no longer had to be up at dawn hoping there would a wonderful sunrise to film, I could just write one. I felt that I was flying, not so much as a wordsmith, but just as a storyteller, which was what I’d always been only in a different medium.

Perhaps another reason why I’d taken so long to write the book was that for much of my life I felt overshadowed by my mother. I felt that I was the less interesting half of that funny double act of my childhood; and as the story became more mine and less hers, I wasn’t sure where to stop. I was carrying on her legacy still in my early twenties, living off my wits and other attributes, and feeling the same wander lust and call to adventure that had hung over my childhood; but knowing that it was still in her slipstream that I travelled.

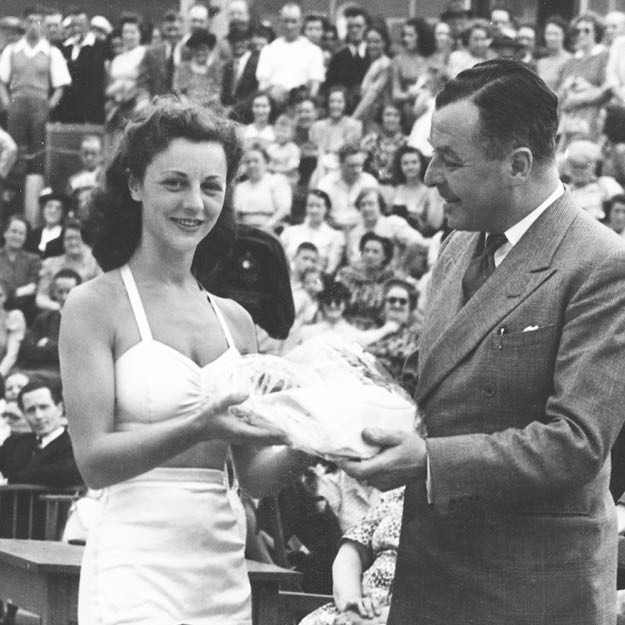

Even in her sixties she was outshining me in many ways – funnier, more charming and the better storyteller. In my twenties I’d spent a heavenly year in Barcelona teaching English, falling in love and making an amazing circle of friends; but I was aware that it was the two nights of her visit which would finally stand out in everyone’s memory. She had insisted on us all going to an old dance hall where she had out rhumba’d and cha cha cha’d all the regular ballroom dancers, until the crowd gathered round her to applaud. I just sat and watched. She was the fabulous dancer, whereas I had my father’s ‘two left feet,’ and as the waiter made a fountain of champagne glasses for us and my lover handed her the top glass, I thought bitterly ‘I’ll always be the one catching the bubbles in the glass below.’ After a year in the city it would be La Mama de Sarah who was never forgotten. The following years, in New York or India, I felt the same – that I was still somehow trying to outdo her but knowing I never would.

Then, eventually I came into my own. I was lucky to have what she had never had – a career. Making arts documentaries allowed me to go back to all those places my mother and I had visited when I was a child, but now I was seeing them through my own lens. I would arrive in Cairo or Los Angeles to find a driver with a sign with my name on it, and be struck again and again by that shift from childhood to adulthood, from powerlessness to power. I began to see that my own strengths as a film maker lay mainly in finding characters and telling stories, and it was an industry in which, if my mother had been born thirty years later, she would have excelled. She would have found the great stories, then persuaded people to take part and told the tales with wit and flair. Like so much that was good in my life I would never have had the career I had if she hadn’t taught me how to rush through open doors, or how to tell a tale.

Even at the very end Audrey was still collecting her extraordinary stories, stashing them away to pull out later to astonish or amuse. This was one of the many gifts she had handed on to me, and now, at last, I could become the storyteller.

I’d needed to wait till later in my life to do justice to a memoir because I needed some self knowledge to understand the debt I had to Audrey. This was never going to be a tale of damage, but rather of a series of gifts. Audrey always pushed open any door and rushed through it, believing that there would be something marvellous on the other side, and she gave me that same belief. There was a sense of delighted wonder, of freely exploring the world and of doors being open to me that has never deserted me. She showed me how to see the magic in things, and that is what I hoped to capture in this book.

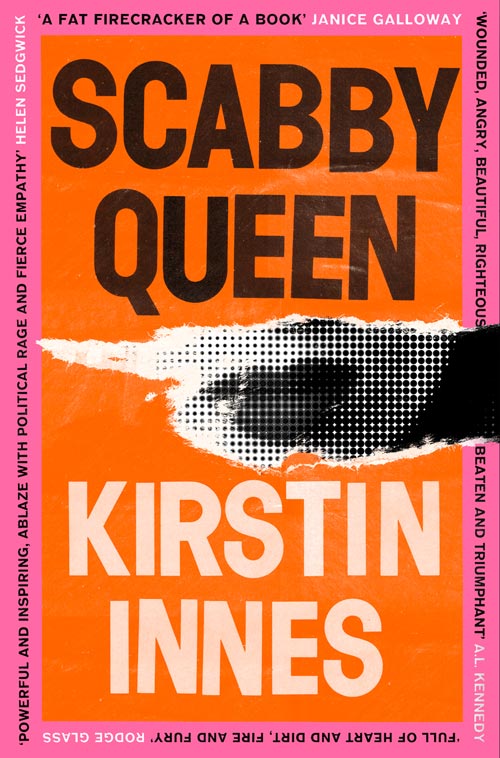

Diamonds at the Lost and Found is available to order now.