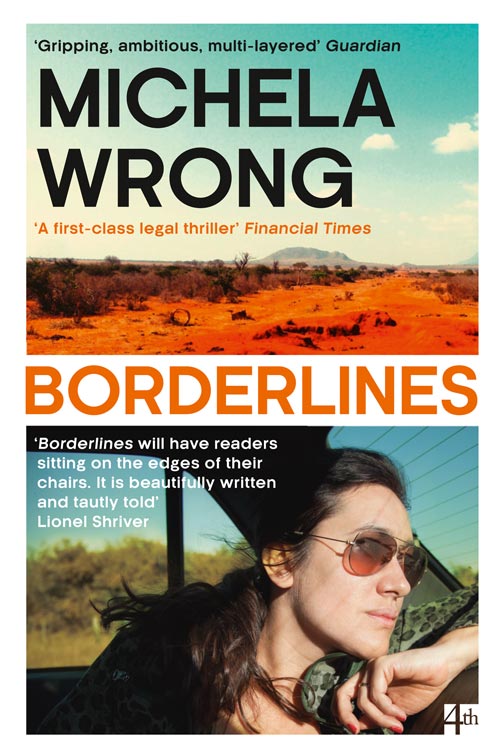

By Michela Wrong

At the close of my novel Borderlines the heroine, a British lawyer who has worked on a border dispute case on behalf of a small state in the Horn of Africa, bumps into a professor from the country concerned, a former friend. She has lost faith in the law, he has gone into exile. The war both of them hoped to avert with a ruling in The Hague is brewing again, with troops building up on both sides and fresh trenches being dug. It’s a sad, bitter-sweet moment.

Last month provided an unsettling reminder of that invented episode, one of those moments when fact and fiction echo each other too closely for comfort. Heavy fighting broke out between Eritrea and Ethiopian troops at Tserona, a small town on the two nations’ contested border. There were reports of Eritreans fleeing to refugee camps, heavy artillery and tanks being used, and possibly hundreds of deaths. The news immediately ping-ponged around social media, passed around by worried members of the Eritrean and Ethiopian diasporas.

Worried, but hardly surprised. Both communities have been braced for just such an event ever since Ethiopia failed to implement a “final and binding” ruling on the border issued by an international boundary commission in The Hague in 2002. Ethiopia’s refusal to pull her troops out was justified by Addis Ababa on the grounds that it needed “dialogue” on practicalities. Tiny Eritrea saw it another way: the ruling had not been accepted, ergo the war with its giant neighbour was not over.

Hence the decision to keep a generation of young Eritreans in military service year after endless year, a policy that has sent thousands of frustrated youngsters fleeing the country. When you see a photograph of desperate men and women clinging to a sinking boat in the Mediterranean, or a cluster of shivering migrants gathered around a camp fire in Calais, rest assured that several Eritreans will be amongst them. In keeping with the butterfly-to-tornado cliché, the failure to implement that border ruling has been vast in its unforeseen human consequences.

My interest in that political stalemate was one of the reasons why I wrote Borderlines. My mother was a primary school teacher, my father a lecturing professor of medicine, so a pedantic streak probably runs through my DNA. I studied history O’ Level at school, and loved it as a discipline, but noticed that only fiction had the capacity to bring the past to life. Once the exam has been sat, most of us forget the treaties and dates we’ve learnt by rote. But you never forget the predicaments of the characters in For Whom The Bell Tolls, The Grapes of Wrath, or All Quiet on the Western Front.

I wanted to write a novel that explained how countries that have gone to war – likely to be an increasingly common event in Africa given how shakily-marked the colonial frontiers are – actually go about agreeing a frontier before the Permanent Court of Arbitration. (The answer involves as many treaties and maps as the lawyers can lay their hands on, bolstered by administrative records, tax and utilities bills and voting lists).

I also wanted to make the point that this, in my view, was no way to end a conflict. The jaundiced learning curve traced by Paula Shackleton, my heroine, as she slowly distances herself from Winston Peabody, the idealistic African-American boss who believes that international justice can prevent bloodshed on sun-blasted battle plains, was also my own. I’ve come to embrace Ugandan academic Mahmood Mamdani’s view that peace settlements only work if they are political, the result of sometimes unappetising moral compromise and canny pragmatism, rather than the application of pure law.

By the end of Borderlines some readers will be surprised to register just how much they now understand about the world of international arbitration, knowledge imbibed – I hope – as painlessly as the bruised Paula falls in love with her millionaire boyfriend. In the post-Rumpole, post-Grisham, post-Good Wife era, our appetite for what would once have been seen as legal porridge, too abstruse for ordinary folk, is surprisingly high. And court cases are intrinsically dramatic, after all, stylised contests in which small teams put worst-case scenarios, in the most articulate language they can muster, to an invisible public.

But I suspect what readers will remember the longest about Borderlines are the characters. Not just the expatriates, bringing their naïve, jarringly-inappropriate expectations to a decaying Italianate capital atop a weathered plateau, but locals like Professor Berhane, diligently researching a contemporary history book, and former fighter Dawit, whose one ambition is to open a cybernet café. Painfully and reluctantly, these residents are registering how, amid the euphoria that followed a victorious independence struggle, personal freedoms were quietly abrogated.

Their choking sense of claustrophobia at a life “cabined, cribbed, confined” as Shakespeare would have put it, by the very guerrilla movement which freed them from alien occupation is the true theme of the novel. And it’s the motif that will ensure that no matter how hard the West seeks to ignore them, the exasperated, angry youngsters of the non-fictional nation state of Eritrea will keep reminding us of their existence.