The Fabric of the World

One of the many enjoyable aspects of Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies is how touchable the world is within: how we can smell, taste and feel those lives of nearly five hundred years ago. The dark hallways and smoky fires, the splash of barge oars in the Thames, the soft leather of unthinking wealth.

In public the cardinal wears red, just red, but in various weights, various weaves, various degrees of pigment and dye, but all of them the best of their kind, the best reds to be got for money. There have been days when, swaggering out, he would say, ‘Right, Master Cromwell, price me by the yard!’

And he would say, ‘Let me see,’ and walk slowly around the cardinal; and saying ‘May I?’ he would pinch a sleeve between an expert forefinger and thumb; and standing back, he would view him, to estimate his girth – year on year, the cardinal expands – and so come up with a figure. The cardinal would clap his hands, delighted.

As a former cloth merchant, Thomas Cromwell notices the fabrics in Wolf Hall with a professional’s eye, and the book follows. When the King’s men arrest Wolsey and seize his belongings at York Palace, Cromwell watches: ‘Bolts of fine holland, velvets and grosgrain, sarcenet and taffeta, scarlet by the yard: the scarlet silk in which he braves the summer heat of London, the crimson brocades that keep his blood warm when snow falls on Westminster and whisks in sleety eddies over the Thames.’ After his years in trade and his years in Wolsey’s service, Cromwell’s way of lifting up those around him is to dress them the part. His mother-in-law accuses him of ‘throwing money at the London goldsmiths and mercers, so the women of Austin Friars are bywords among the city wives’, and he welcomes a new servant into the house by mentally dressing her for her new life there: ‘He takes her out of cheap shrunken wool and re-dresses her in some figured velvet he saw yesterday, six shillings the yard. Her hands, he sees, are skinned and swollen from rough work; he supplies kid gloves.’

Cromwell himself is careful with his own costume. He stays in black, shadowy, invisible, expensive but always understated, careful to always be the watcher, not the show: ‘At court and in the offices of Westminster he dresses not a whit above his gentleman’s station, in loose jackets of Lemster wool so fine they flow like water, in purples and indigos so near black that it looks as if the night has bled into them; his cap of black velvet sits on his black hair, so that the only points of light are his darting eyes and the gestures of his solid, fleshy hands.’ At Anne’s coronation, when she insists he sports the crimson of his previous master, the Cardinal, Cromwell obliges by wearing a crimson so black that one of her party calls him ‘a travelling bruise’.

Colour and fabric permeate WolfHall. The golden-blue of crisp days, and the seven hundred yards of blue cloth Anne walks to be crowned; blue silks and satins of wrapped gifts and ambassadorial fashion; the green of forest light and Anne Boleyn’s Maid Marian outfit, clean apples on white paper, and artfully displayed stockings to draw the mind from the business at hand; the yellows of a happy marriage bed and child- hood dressing-up.

Throughout, characters are reflected in the cloth around them, as befits a citizen of the sixteenth century: while Wolsey’s vivacity and largesse show themselves in his rich outfits, Thomas More’s narrow life experience betrays itself in the new carpet he wishes to display. When Cromwell inspects it, at More’s invitation, he finds ‘the ground is not crimson but a blush colour: not rose madder, he thinks, but a red dye mixed with whey’, and the whole is actually two carpets sewn together. It’s another material indulgence More has missed out on, ignorant to worldly pleasures right up to his execution in the cold rain.

As Cromwell climbs the court ladder, discovering his capabilities and how he might build a whole domain to appreciate them, everything looks fresh and new, ready for a golden future: ‘Where the light touches flesh or linen or fresh leaves, there is a sheen like the sheen on an eggshell: the whole world luminous, its angles softened, its scent watery and green.’

Anne’s seduction, marriage and coronation are illuminated with textiles and colour: rooms at Whitehall with wall hangings of silver and gold cloth, and an embroidered satin bed-hanging; pre-coronation rooms at the Tower painted with ‘quicksilver and cinnabar, burnt ochre, malachite, indigo and purple’; and the day itself a blinding parade of knights in blue-violet, lords in crimson velvet, Anne in ‘a white litter hung with silver bells’, with ‘blossom mashed and minced under the treading feet of the stout sixteen, so scent rises like smoke’.

Dizzying perfumes and textures saturate the pages: damask, brocade, furs and silks, velvets and lace, gloves and ribbons and smocks and robes, ermine and gilt, rosewater and cinnamon. Life is sweet, and rich, and good things abound.

But as Wolf Hall closes, the colours are dimming, the texture coarsening. The yellow of a warm home has soured into the ‘jaundiced yellow’ eyepatch of an enemy, and the memory of the yellow feet of the poor that still nauseates Henry, years on. Golden-green sunlight has become grey drizzle. Cromwell now dwells on bones, skulls and stones, nailed-down coffin lids and burial parties, the feeble sun and piercing winds, and More’s prayer book, which comes with- out gilt-edging but which instead is checked for blood specks.

And so the scene is set for Bring Up the Bodies, which opens only two months later, but in an entirely new sphere. From the outset, this changed landscape – where a man may dismiss his wife of twenty years, take another, and behead her a few months on – is streaked with gore. The falcons of the royal party watch with ‘a blood-filled gaze’, returning to Cromwell with ‘flesh clinging to their claws’. The colours are of painful sunburn, and Cromwell’s unnerving, unnatural paleness, the silvery pallor of Jane Seymour, the King’s burst veins and greying hair. And the view of the world has tilted, shifted: even through the sylvan make-believe of the King’s party as summer turns to autumn, the fabric now is always, always, human tissue and violence: smashed icons, smashed teeth, smashed heads; walls that cannon could pierce like paper; obliteration, eye gouging, throat cutting, blood on the wall, blood in the bed, blood on the floor. Instead of plush, deep fabrics, there are iron daggers, lances and jaws, axes, swords, pike and halberds, gunpowder and steel, stone and metal.

Anne’s outfits reflect this change, too: ‘Anne was wearing, that day, rose pink and dove grey. The colours should have had a fresh maidenly charm; but all he could think of were stretched innards, umbles and tripes, grey-pink intestines looped out of a living body … The pearls around her long neck looked to him like little beads of fat, and as she argued she would reach up and tug them; he kept his eyes on her fingertips, nails flashing like tiny knives.’ As her fate approaches, Cromwell’s eyes are often drawn to Anne’s rubies, red against her fine, pale neck. Her brother, George, dons similarly prophetic outfits: ‘Today he wears white velvet over red silk, scarlet rippling from each gash. He is reminded of a picture he saw once in the Low Countries, of a saint being flayed alive.’ And as the inventories begin coming in from the abbeys, they also hold hints of what is soon to come: ‘Two altar cloths of white Bruges satin, with drops like spots of blood, made of red velvet. And the contents of the kitchen: weights, tongs and fire forks, flesh hooks’. Even the kitchen implements talk of suffering.

In the few months that Bring Up the Bodies covers, the sun rarely seems to shine. It is a cold winter and grey spring of shadows and wet wool, candles and draughts, when the puddings on the table themselves contain violence, with Cromwell’s cook serving up a miniature red and translucent battlement, complete with edible archers on ‘airy stone and bloody brick’. After the fire in her rooms, Anne is no longer yellow, but grey; Cromwell’s servants sport mottled grey uniforms; courtiers roll into rooms like formidable metallic siege engines, and days end ‘broken off, snapped like a shin- bone, spat out like smashed teeth’.

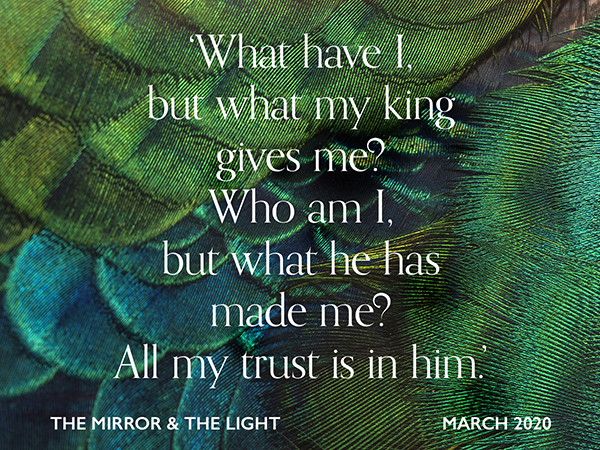

Cromwell’s England of 1536 is hardening for battle, priorities turning from domestic comforts to hoarded gold and forged iron. But in the days to follow, who will be Cromwell’s enemy, and in what colours will they come?

The Mirror and the Light is out now.