In college, a professor introduced me to a long eighteenth-century poem by James Thomson called The Seasons. Tremendously influential in its time, it is a lyrical and expansive description of the countryside. There is an entire language here that attends to and celebrates the natural world, and reading it, the salient feature is how rare that is. This is a loss, because it’s probably good for a person, to feel for wild places and to see them clearly. We treat this appreciation as something that comes naturally, but like anything else, you’ve got to learn it.

It has long been noted that you cannot persuade a person of global warming. The idea of global warming is predicated on the belief in the earth as a place very different from our everyday experience, which is often of streets and porches and backyards and apartments. These places are important––but sometimes we have need of seeing beyond, to a wider world. For many of us, it is hard to believe that the place we live is a planet, and that it is in danger, because to most of us, it does not seem to be true, and if true, it’s frightening. Our lives consist narrowly of human things and we’re ill-prepared for a threat so far out of left field. This is a tragedy, and an illustration of how little attention we pay to the outside world. Global warming, if we are to solve it, becomes a problem of seeing the world anew.

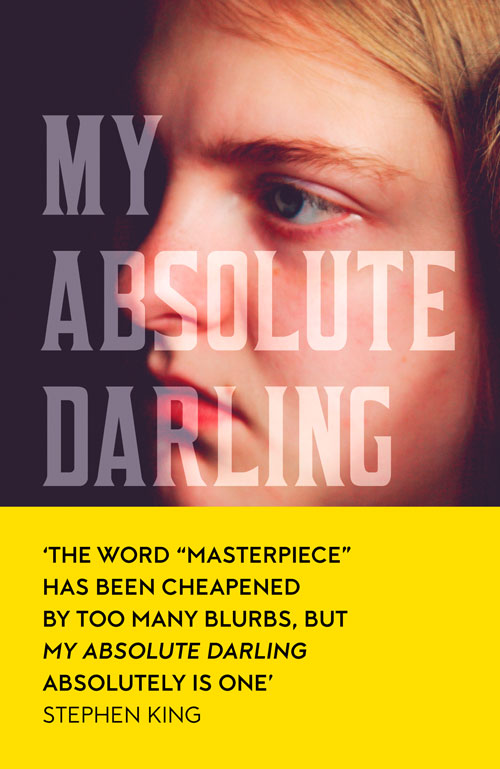

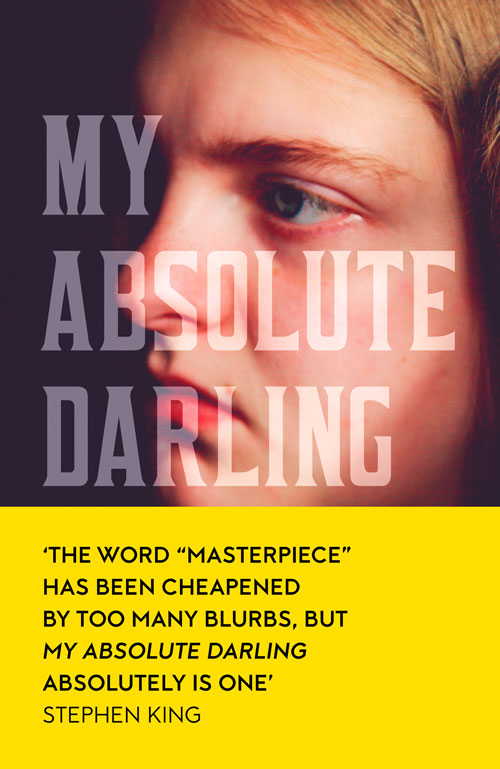

I thought about that a lot while writing My Absolute Darling, because Turtle is deeply rooted in place in a way that is rare. She is a wounded person. The hurt that has been done to her is, to her, inscrutable. She can make no sense of it, and to begin making sense of it, she must pit her own judgment against the part of herself that loves her father. It is, in some ways, her very selfhood, her personhood that is under attack. I think most of us have seen people who could never be more than their old, childhood injuries. There are people in whom the hurt is too deeply rooted. That is what is at hazard. And, in some ways, it is Turtle’s sustained and attentive relationship to the world beyond herself that saves her. If her father is too hurt to think of anything outside of himself for very long, Turtle is a different, and a more observant person, better able to see herself, better able to reason through her own mind. In this project of seeing clearly, of observing closely, her wilderness fastnesses are her best and most enduring tutors. I remember very clearly as a child loving the places I found. Loving the ponds and the stony creeks and the redwoods. I remember how it felt, finding pacific giant salamanders in stream banks. It felt like a miracle. The wilderness is the dominant source of love and wonder in her life. Her life takes place in a very different setting.

So part of what I wanted to do with this book was to capture what is so alive and important about the American Northwest. Turtle lives in and attends to a world that has fallen somewhat from the cultural discourse. Her everyday life is deeply rooted in a wilderness that is hard for many of us to imagine, and her story unfolds in a setting alien to many of us. Otherwise, we would not allow these places to be destroyed, and otherwise, there would be no difficulty seeing the danger posed by global warming and mass extinction. I wanted to make a place that is meaningless to most of us, I wanted to make that place meaningful and real to the reader. I guess my hope was to put some of those places on the page, and to help you feel their urgency, as something you had perhaps not seen before. I felt there was value in that, as there was value for Turtle, in a seeing a world that is outside of ourselves.