Today is #BallardDay, J.G. Ballard’s birthday and 4th Estate’s annual celebration of all things Ballardian. This year we asked our staff – as well as some famous Ballard fans – to tell us about the Ballardwerks that had the greatest effect on them. From ecological SF early works like The Drowned World to the near-future mystery of Super-Cannes, their choices are testament to a writing career that flourished for almost 50 years…

MIRACLES OF LIFE

MIRACLES OF LIFE

Jim Ballard was one of my favourite authors but his old-world charm and avuncular appearance were deceptive as he couldn’t have been less conventional.

His radical and unpredictable take on all aspects of life was always riveting and there was never a shortage of journalists keen to visit his infamously un-modernised semi in Shepperton to interview him. Although he avoided the literary world (and refused to take part in festivals), Jim took a practical interest in his publicity when a new book was about to be published and during the many years I was his publicist, from the publication of his autobiographical novel The Kindness of Women to his final memoir Miracles of Life and all his disturbingly brilliant novels in-between, I would work closely with him planning the campaigns. The resulting media coverage was always extensive and a celebratory lunch at the River Cafe became a tradition and then Jim would disappear back to Shepperton until his next book came along. He was a lovely man.

Helen Ellis, Ballard’s Publicist

THE ATROCITY EXHIBITION

THE ATROCITY EXHIBITION

Above all, The Atrocity Exhibition is a melancholy book, fixated on something terrible that it can’t let go. Its landscape is both dead and accelerating, a windblown desert strewn with the wreckage of modernity that is at the same time a place of unbearable speed and intensity. In 1964 Ballard’s wife Mary died suddenly of pneumonia, leaving him to bring up their three children alone. In 2007, when he was already terminally ill, I interviewed him. ‘I was terribly wounded by my wife’s death,’ he told me. ‘Leaving me with these very young children, I felt that a crime had been committed by nature against this young woman – and her children – and I was searching desperately for an explanation . . . To some extent The Atrocity Exhibition is an attempt to explain all the terrible violence that I saw around me in the early sixties. It wasn’t just the Kennedy assassination . . . I think I was trying to look for a kind of new logic that would explain all these events.’

Hari Kunzru, Author

CONCRETE ISLAND

CONCRETE ISLAND

I did not understand when I was a boy that the best way to prepare for my adult future would be to read the work of J.G. Ballard. That authors offering me generation starships and galactic empires were a distraction: that it was Ballard who was writing the world I would grow into. I don’t think I understood that until the crash-death of Princess Diana, and I knew that I had been here before, and in whose pages. Concrete Island is of its time, an artefact, but one could write something very similar now. One would need to deal with the mobile-phone issue – probably destroy it in the initial crash – but I wonder how many of us would actually stop, or let anybody know, if we saw the filthy man in the motorway island, and how many of us are able to escape the islands on which we now find ourselves marooned.

Neil Gaiman, Author

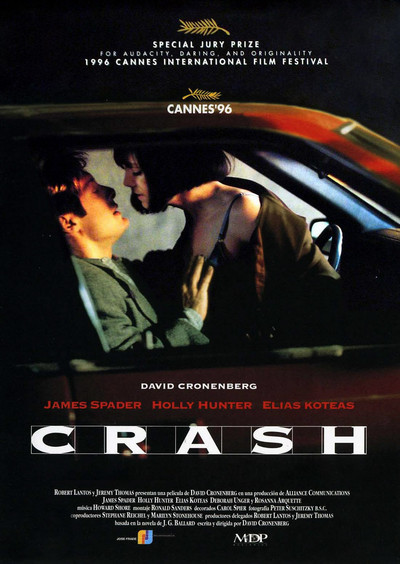

CRASH

CRASH

My first exposure to J.G. Ballard was through a film, not a book: David Cronenberg’s controversial 1996 adaptation of Crash. I was fifteen at the time and the film was causing a hysterical reaction everywhere you would usually expect it. Looking back, I’m not sure why, but I was desperate to see it at the cinema and didn’t let the 18 certificate put me off. Along with three older friends we set off for the dizzying glamour of the Tower Park leisure complex in Poole. To try and look old enough to get in, I did what every teenage country boy usually does: dress like you’re heading for a big night out in a provincial small town nightclub. This was a bold look for a Saturday afternoon, but it worked. I was in and when the film started to roll, I was gripped and the film set me off into a lifelong fascination with Ballard’s books. I hope Ben Wheatley’s extraordinary adaptation of High-Rise does the same next year and blows the minds of the next generation of future Ballard fans just waiting to be awakened.

Matt Clacher, Marketing Director at 4th Estate

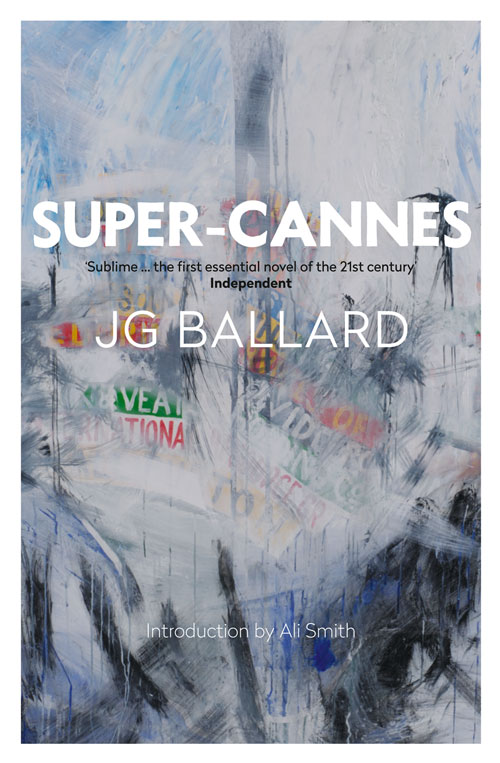

SUPER-CANNES

SUPER-CANNES

‘There’s something about the novel that resists innovation,’ J. G. Ballard said. He said it more than once; it was something he was fond of saying even as he himself innovated,working away beneath and pulling up the floorboards of literary tradition, one eye on the contemporanea his novels happened to inhabit and the other on a very different clock, one ‘whose movements are virtually imperceptible but which cover giant periods of time as the human race evolved.’ Super-Cannes, which he published on the cusp not just of a new century but a new thousand years, makes inquiry into both – the time we inhabit and our place in evolutionary terms. It parallels the ancient mysteries of Eros and Thanatos alongside what’s called human progress. It rewrites (it seems literally to do this as it unfolds) the speed and expectations of English narrative while examining our warmth towards, our desire for, and the naivety and comfort in our nostalgia about, the novel form.

Ali Smith, Author

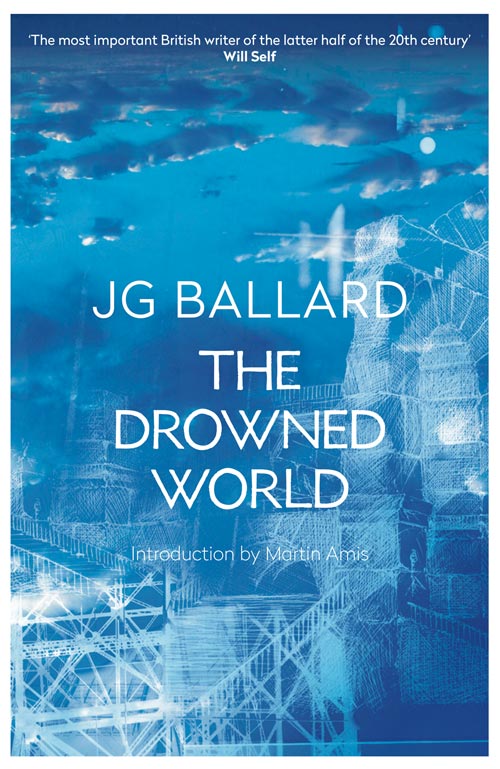

THE DROWNED WORLD

THE DROWNED WORLD

I read my first Ballard far too young, at the age of about twelve, finding The Drowned World on the bookshelf next to John Wyndham’s The Day of the Triffids, which I’d loved. It could be argued that both books depict ‘cosy catastrophes’, the term Brian Aldiss coined to describe that genre of science fiction in which white, middle-aged, middle class men find themselves rather enjoying the apocalyptic scenarios they find themselves in. Certainly, Dr Kerans seems to thrive in the submerged streets of this near-future London, and as a child I thought I might like to join him among the gymnosperms. Pootling around in a boat on Oxford Street didn’t seem half as scary as the idea of malign sentient plants. But as I’ve grown older, and the effects of climate change have grown more palpable, The Day of the Triffids seems like about as terrifying as an Enid Blyton story, while The Drowned World becomes more plausible with every inch of sea level rise. I later went on to obsess over Ballard’s concrete islands, his atrocity exhibitions, his high-rises, and all the films, music and architecture that went with them. But for me, his most beautiful and terrible landscape will always be that flooded tropical version of the city I live in.

Tom Killingbeck, Publishing Executive at 4th Estate

HIGH-RISE

High-Rise was the first Ballard book I ever read. It took me a couple of hours to get through it, on account of it being so sickening (and riveting) that I couldn’t tear myself away from it. Or eat. Not because the book is grotesque, or disgusting, or gorier than I can take, more that I can start to see a future like the one presented in the book actually happening; one where class and status takes precedent over everything; over logic, over reasoning, and over proper societal structures that condemn violence. When I finished the book, I thought long and hard about how I’d fare in a High-Rise situation. I still don’t have a concrete plan of action, but I know that I definitely wouldn’t eat a dog. Nor would I fall in love with any member of my family.

Candice Carty-Williams